Last Updated on May 6, 2021 by Bo Jacober

On February 24, 2021, Zoom announced it was making live transcription available on free accounts. Prior to this announcement, Zoom’s captions were available only to paid users. If users dependent on captions couldn’t afford a paid account, they were excluded from participating in virtual meetings held over Zoom. This impacts users with deafness or hearing loss, auditory processing disorder, and those holding meetings in a language other than their native tongue.

In the words of Shari Eberts, a hearing health advocate and the founder of LivingWithHearingLoss.com who started an online petition with over 80,000 signatures demanding free captions on video conference services,

Should wheelchair users pay to use ramps? Of course not, because ramps provide them equal access to buildings and public spaces. They allow wheelchair users to navigate the world successfully and independently.

For those of us with hearing loss, captions are our ramps.

Reactive, Not Proactive

Zoom’s announcement comes fourteen months into the COVID-19 pandemic, a pandemic that has sent the demand for video conferencing skyrocketing. While Zoom boasts about providing “a platform that is accessible to all of the diverse communities we serve”, the arrival of a free real-time transcription came only after Zoom was hit with a December 2020 class-action lawsuit for violating Title III of the federal Americans with Disabilities Act.

Recent history suggests this lawsuit could be successful. In November 2019, Harvard University settled a class-action lawsuit filed by the National Association of the Deaf objecting to the lack of captions in Harvard’s Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). The settlement requires Harvard to take a more proactive approach in captioning videos, captioning all media whether or not accommodation requests have been made by disabled users. In addition, the settlement notes that captions must be accurate to be equitable; automatic captions have too high an error rate to provide true accessibility.

Requirements for video conferencing are different than those for prerecorded media or live presentations. Guideline 1.2.4 of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), for example, requires captions for live presentations, but not for multimedia conferencing. Still, to truly accommodate users who depend on captions to participate in video conferencing, Zoom needs to take a more proactive approach instead of providing the bare minimum in the face of public pressure.

But Are They Captions?

Zoom’s automatic transcripts provide an estimated 80% accuracy rate, far below the threshold for providing an accessible experience. But even if they were more accurate, do Zoom’s captions do their job as captions?

While captions can be most simply defined as an onscreen transcription of spoken audio, a blog post by Erin Myers of rev.com on the differences between subtitles and captions additionally notes that

Captions are of particular use to individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing as they include background noises, speaker differentiation, and other relevant information translated from sound to text.

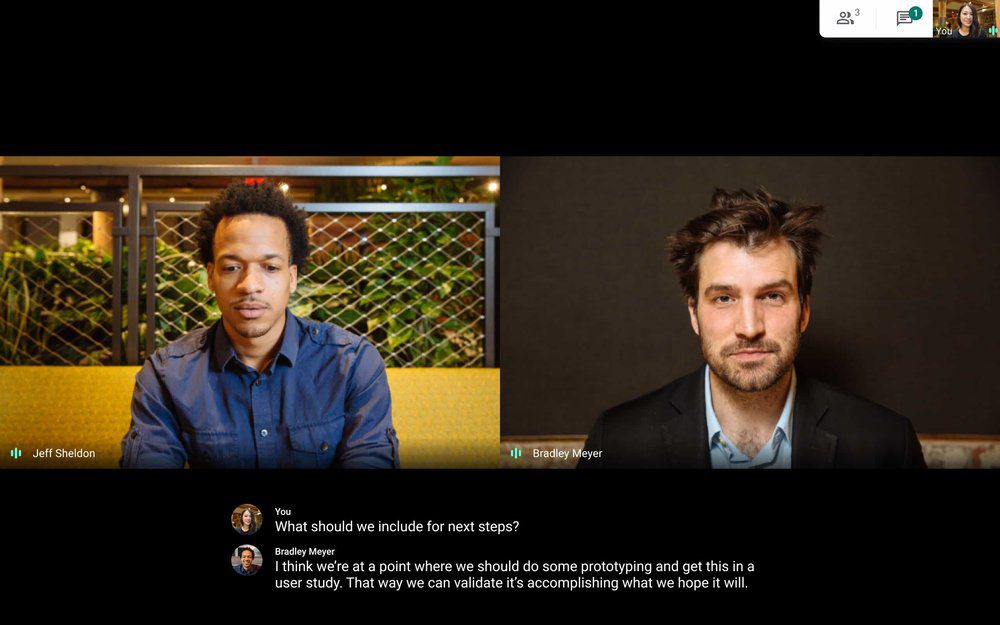

Speaker differentiation means identifying the speaker by either placing the caption underneath the speaker, or including the speaker’s name alongside each block of text. In an April 2020 test of video call captioning services, author Meryl Evans describes the speaker differentiation feature in Google Meet conferences as a “game changer”, as well as praising Google Meet’s captioning performance in a personal video call.

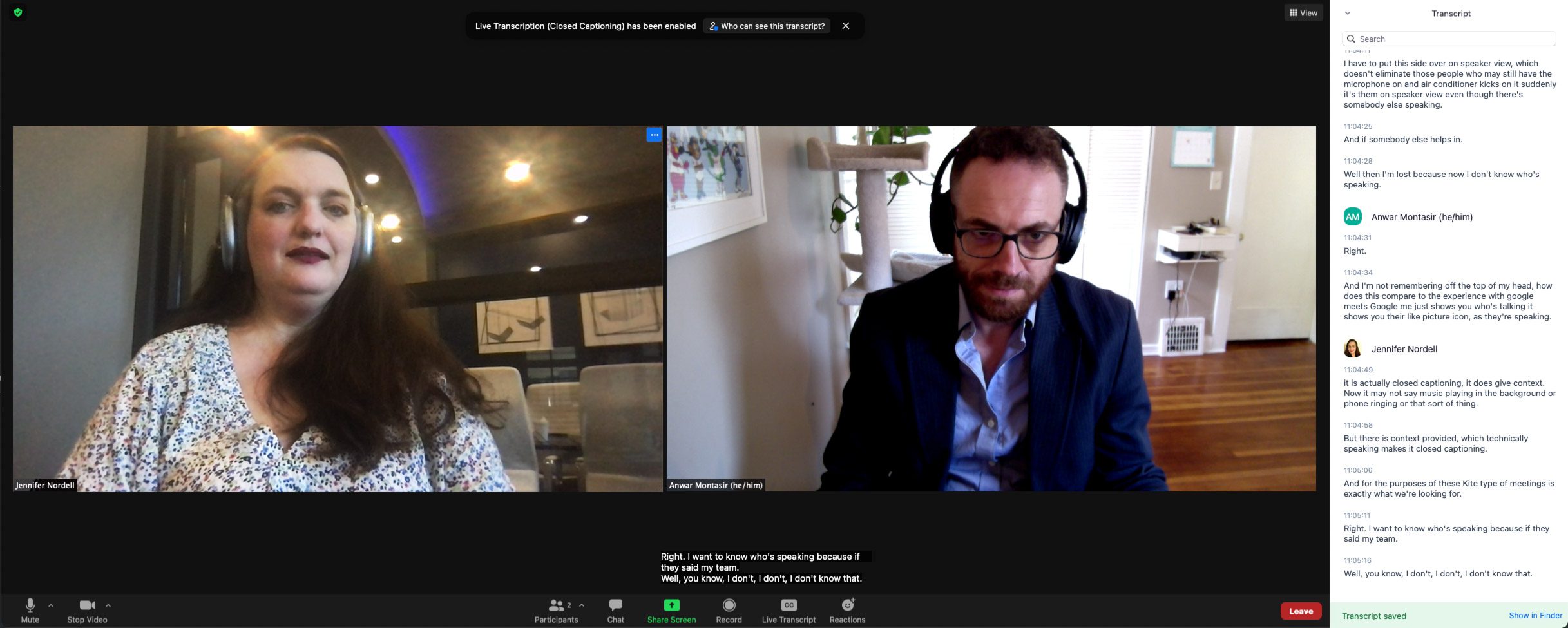

Conversely, Zoom offers no speaker differentiation, just a cluster of text at the bottom of the screen. While users can attempt to identify the speaker by viewing Zoom’s live transcript feature, this pulls the user’s attention away from the call itself, making it difficult to keep up or to focus on information shared onscreen. In addition, in a call with my Treehouse colleague Jennifer Nordell to test this feature, the live transcript was highly error-prone, frequently attributing Jennifer’s words to me or vice-versa.

And this was in a call with just two people! Imagine a conference call with a dozen coworkers present, and someone says “my boss says you need to get this done immediately.” If you have no idea who is speaking and who is being spoken to, an everyday sentence becomes a cause for high anxiety.

Moving Forward

Making Zoom better starts with two steps:

- Improvements to Zoom’s products should be motivated by a desire to include disabled users in every conversation, not by fear of losing a lawsuit.

- The needs of disabled users should be included in every stage of the product design and development process, especially user testing.

Until that happens, Treehouse will be sticking with Google Meet for our video conferencing.